How do YOU save your photos?

A generation ago this would have been a silly question – in a photo album, of course! Then came the digital evolution.

Most people use the familiar JPEG format, but there are other ways of saving images. Photoshop gives us some twenty options. Though most of them are archaic or niche formats, it is comforting to know that we can retrieve images written by any obscure or ancient piece of software. However, there are a handful of useful for mats for storing our images, each one with its own strength and you’ll want to use them if you value your photos. Let’s start with the most common one.

JPEG (Joint Photographic Experts Group)

The vast majority of digital camera shots are taken in JPEG mode. The main advantage of this file format is the smaller file size.

Let’s do the math: an 18 Megapixel (MP) camera – fairly standard in today’s world – will give you around 5200 x 3466 pixels which translate into a hefty (uncompressed) 51.6 Megabyte (MB) file. The JPEG format can easily apply a compression of around 10:1 to 20:1 without any visible quality loss. Even a compression of our 18 MP shot to 0.8 MB (65:1 compression) will give you decent results! This sounds much more manageable. Also keep in mind that your camera can write those smaller files a lot faster to the memory card.

JPEG works with lossy compression, which means that information gets thrown away. If quality is of prime importance then use the highest quality setting on your camera. Quality loss won’t be apparent in small prints, but can become a problem with larger sizes. People often wonder why their image files have different file sizes, coming from the same camera. The reason is that some images are easier to compress than others.

It is very important that you don’t save your images repeatedly as JPEGs - each time you save them, the image degrades further. Of course, your JPEG camera files can be copied to your hard drive, moved around and archived with no quality loss. You can open and view them as often as you like – they won’t deteriorate. However, after any editing step they should be re-saved in a file format that doesn’t compress them again, for example as a TIFF file.

Other file formats for the internet

JPEG is really all you ever need when you email your shots, upload them to social media or post them on a website. However, there are some other formats and they can be handy in some situations.

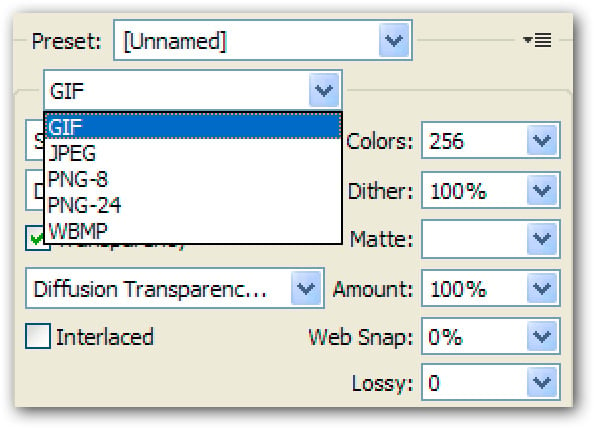

Use the GIF format for files with solid blocks of colour. This is ideal for line art and logos, which don’t need millions of colours. Choose ‘CompuServe GIF’ from the ‘Save as’ interface under the ‘File’ menu. GIF images only support a maximum of 256 colours though and are therefore not good for photos.

One beauty of GIF files is that they allow for transparency. If you want to blend a logo seamlessly into the background of a webpage, then GIF is the way to go. Then there is the option of storing multiple images in one file, giving you an animated display

There are more file options for the internet: PNG-8 also allows for transparency, however, older web browsers don’t display PNGs properly and stick a white background behind them. Similar to GIF, they only allow for 256 colours. The PNG compression is lossless and you get higher-quality files at smaller file size than with GIF

Another format is called PNG-24. This is the ultimate in web quality. It gives you all 16.8 million colours and 256 levels of transparency, which you need if you want to include drop shadows. If quality is more important than download speed, then go for PNG-24.

TIFF (Tagged Image File Format)

Now we move to the file formats which are used for day-to-day work with images. They don’t use compression, at least not destructive compression.

TIFF was developed in 1986 – a very long time considering the rapid advance of computer technology. We can expect TIFF files to be around for some time to come. This file format is a pretty safe bet for long-term archiving.

TIFF used to be a very straightforward format, containing only the information on the actual pixels, the output size and resolution. In the latest versions, Photoshop allows you to save TIFF files with pretty much anything you can throw at them – layers, vector data, clipping paths, spot colour channels, etc. But beware, just because you can save the data doesn’t mean that other programs can read them!

There is a choice for LZW and ZIP compression, both lossless, but you are not saving much space and it takes longer to read and write those compressed files.

PSD (Photoshop Document)

Every image editing program has its own ‘native’ format and this happens to be PSD for Photoshop and Elements. It used to be the only file format that could handle layers, alpha channels, paths, etc. This is not the case anymore, but many people grew into the habit of storing their layered files in PSD and the flattened versions as TIFFs. This is as a good habit, even if it is just for the sake of sound housekeeping.

PSD works with a lossless compression and by default Photoshop saves a flattened composite of the image to “maximise file compatibility”. This will again increase the file size of files with layers, but it is recommended that you leave this option on to make the files readable to other programs.

You might have missed a discussion on RAW files; however, the camera RAW format is simply a storage bin for the raw data collected by the imaging sensor. It is not really an image format and we’ll discuss RAW and DNG (Digital Negative) files another time, in connection with Raw conversion.

So, which file format should you use? There is nothing wrong with compressed JPEG files, just don’t save them repeatedly as JPEGs. For repeated saving and archiving you are best off with one of the uncompressed image formats. In the next issue we’ll look at what media you should use for archiving your photo collection.